Ah, January. The month where we collectively resolve to drink less, exercise more, and become the kind of person who actually enjoys quinoa. But for those of us with ink-stained fingers and overburdened bookshelves, the new year offers something more tantalising: a chance to recalibrate our creative lives. And, let’s face it, if anyone needs resolutions, it’s us — we who spent December binge-watching a Netflix series “for research” or Googling “how to write a novel in two weeks.”

So, in the spirit of renewal, here are some literary and creative resolutions that might make 2025 your most inspired year yet.

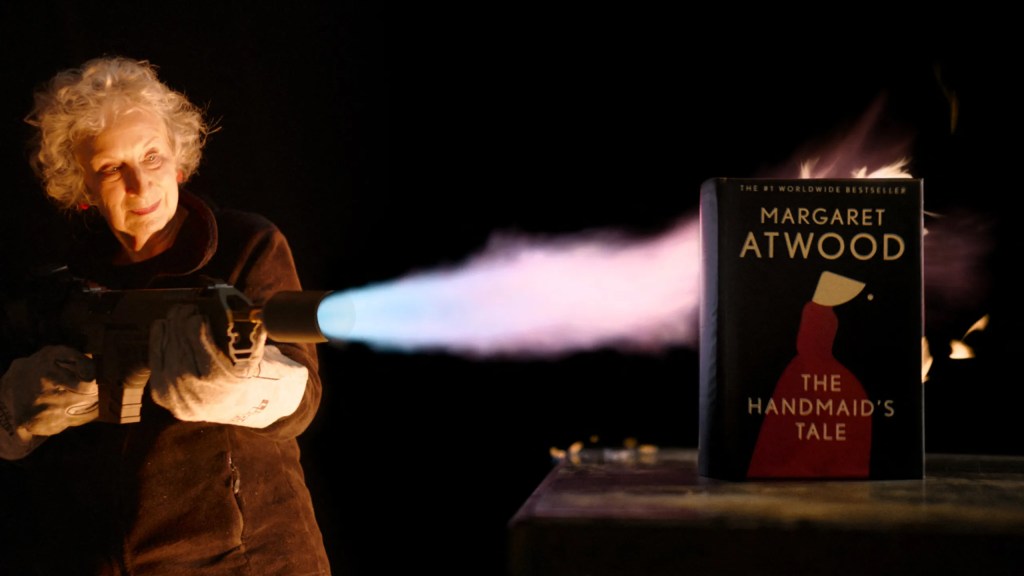

1. Fight back against AI’s copyright encroachments

The rise of generative AI is a bit like the plot of a dystopian novel — machines devouring our creative output to regurgitate it as lifeless mimicry. And while it might be tempting to shrug and say, “Well, at least they can’t write proper dialogue,” the existential threat to creatives is real.

Here’s a resolution: educate yourself and get involved. You could start by supporting independent publishing collectives like Breakthrough Books, who have been set up (in part) as a creative revolt against the threats of AI. If you’re UK-based, you could also contribute to the government’s consultation on AI and copyright. The policies being shaped now will determine whether Big Tech gets free rein to plunder our work, or whether creatives retain some semblance of control over their intellectual property. Speak up, because the machines can’t (yet).

2. Read differently

Yes, everyone’s banging on about reading more, but quantity isn’t everything. This year, resolve to read differently.

- Genre-hopping: Are you a literary fiction purist? Try a science fiction classic. A crime thriller junkie? Dip your toes into poetry. Expanding your horizons could unlock new inspiration for your own work.

- Slow reading: Let’s reclaim the joy of savouring words. Pick up a pen, underline passages, and take your time — even if it means finishing only half as many books. (That’s right, Goodreads, we said it). The joys of simple doodles and marginalia are not too be dismissed.

- Support the little guys: Swap Amazon’s algorithm for our curated lists of independent publishers (here and here). Your bookshelf will thank you, and so will the literary community.

3. Support your local library

Neil Gaiman once said, “Libraries are the thin red line between civilization and barbarism,” and who are we to argue with Gaiman? Libraries aren’t just places to borrow books; they’re community hubs, refuges, and fountains of inspiration. If you want your library to still exist in 2026, resolve to support it now. Borrow books, attend events, and loudly advocate for funding. For more on why libraries matter, revisit our love letter to them here.

4. Buy less, create more

Sure, it’s tempting to splurge on the latest Moleskine planner or an overpriced “productivity” app, but let’s be honest: the tools aren’t the problem. This year, resolve to spend less time shopping for inspiration and more time creating. Paint, scribble, or start that novel — with whatever you already have on hand. The magic isn’t in the notebook; it’s in you.

5. Find (and nurture) your creative community

Creativity can be isolating, especially when you’re staring down a blank page with nothing but self-doubt for company. Resolve to find your people this year. Join a local writing group, share your work online, or just meet a friend for coffee and complain about how hard writing is. Collaboration and camaraderie are fuel for the creative soul.

6. Rediscover play

Remember when you created purely for fun? When writing terrible poetry or finger-painting felt like a triumph, not a failure? Make space in 2025 for playful creativity — try a new art form, experiment with zero stakes, and remind yourself why you fell in love with creating in the first place.

7. Submit that project

Remember when Shia LaBeouf told us to “just do it” and the internet – for whatever reason – went crazy for the idea? If you’ve been holding off submitting your illustrations to that agency or awards, if you have a novel sitting gathering proverbial dust when it should be in front of a publisher, or a short story desperate to be read, make 2025 the year that you actually submit your work. We, for one, are open for submissions, and we’d take a 10,000 word article or an artistic collage on the merits of ankle socks provided it is executed well. Take a chance and tap us up – or reach out to the plethora of other brilliant independent publishers, creative agencies, etc., who are out there.

As the calendar turns and the blank pages of 2025 stretch out before us, let’s resolve to make this year not just productive, but meaningful. Support the people, places, and principles that make creativity possible—and, above all, keep creating. After all, no one’s writing the dystopian novel of the future quite like you.